You’ve been kidnapped, and there’s a little crack of light over there, so wriggle towards it (your hands are tied, too). You nudge open what feels like a curtain with your nose and see an ordinary street scene: shops, cars, trees. Notice how your eyes are taking everything in, feverishly. Thrumming with adrenaline, your brain is processing visual information in double time: where am I? What time is it? How far have I gone? Through the glass (there’s glass) you can’t hear or smell anything, either, so your eyes do all the work. That took about two seconds. (By the way: you weren’t kidnapped, you fell asleep in the back of your mum’s car).

Photography works like that sudden exposure of illuminated information – it literally does, and it’s worth drawing back every time to those early, spectral appearances of the outside world, inverted, in camera obscuras. To paraphrase the great Eric Carmen, eyes attuned to look at photographs are hungry eyes. They need to be: every photograph is as much a no as a yes, as much a blocking-out as a revelation. Give a rat an orange and he’ll gnaw every last fibre (trust me). Your eyes do the same with Beth Herzhaft’s series she calls “area photographs”. Each is a cropped sliver of information: life through a letterbox.

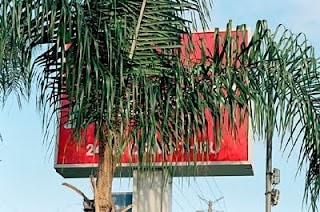

The title “area photography” brings up associations of the geographic survey: images used, maybe, to plot out the visual coordinates for development or demolition. Yet Herzhaft’s images deliberately frustrate specifics. It’s sky or land, but not both. There’s no corner-of-the-eye, or else it’s all corner-of-the-eye. Take ‘Untitled Area Photo, Glendale’ (2007): a big red billboard, of the sort associated with the webs of road around southern California, is blocked by a shaggy palm tree. Just about readable at the bottom of the sign is the legend 24 HOUR DRIVE-THRU. The cursive loops of the tree’s leaves become a kind of natural graffiti, blotting out the man-made intrusion on the landscape. You’re seeing it from a car, let’s assume (this is southern California, after all, and the angle’s about right); yet the sign, promising escape from the drudge of the road, can’t reveal itself, despite filling the field of vision. So it’s an image of deferred evasion: you can’t not look (what else is there to see?), but can’t quite make sense of either place or promise. Your brain bangs against a wall.

Image courtesy of Beth Herzhaft

Herzhaft’s photographs depend upon a reduced visual field that recalls Stephen Shore or William Egglestone’s fascination with the spoils and trappings of a country grown fat on itself. Her interest, though, is in the way oddities in the landscape reveal themselves, in the way the cultural devolves to the natural. Slits and gashes in a fence become the toothy grins of cartoon monsters. A bulbous bag of rubbish, tied with a weirdly pretty green bow, reveals a red logo like a pulsing heart. And in her two photographs of trees, lengths of rubber hose hang from branches like sad little animals trying to gain purchase. In one, ‘Untitled Area Photo, Calabasas’ (2007), the orange tubing is tied around a sawn-off stub; not strong or tight enough to support anything, it hangs there, its blazing look-at-me colour at odds with its evident uselessness. What’s it for? Where am I? It’s a credit to Herzhaft that you keep wanting to find out, despite knowing that you never will. Bang bang bang bang bang.