“Time-based art” is a great new contemporary art phrase to drop into conversations, with the redoubtable Orwellian tautology of “movement-based dancing” or “sound-based music.” It’s one of those phrases that sounds neat but falls apart when you try to grasp it, like a stale meringue. All cultural endeavor is, by its very nature, time-based. After all, the 400,000 year-old Moroccan “figurine” discovered in 2003 (nominally the world’s oldest extant sculptural object), which is about as far away from contemporary art discourse as you can get on this planet, is intrinsically time-based — it exists in time and cannot be experienced immediately. Nonsensical though the phrase might seem, it does represent the good intentions of curators and academics to discuss a strain of contemporary art not satisfactorily contained by the term “video art” (nor its painfully literal cousin, “lens-based art”). The urge to categorize and identify is one of those Enlightenment hangovers we thought we’d shaken off, like Corinthian columns and powdered pompadours.

A new installation by John Gerrard, an Irish artist whose work is most often described as “time-based” (there’s not a lot of precedent for what he does, and calling it “video art” or “virtual art” isn’t quite accurate), opened this week in the Canary Wharf underground station. The station is a cavernous raw-concrete and steel Norman Foster construction completed in the late 1990s, set in London’s principal financial district. Canary Wharf creates the city’s only homogenous skyline as well as a catch-all visual metaphor for the flow of international capitalism. Its spiky towers, like the busted teeth of old robots, formed a prominent backdrop to recent scenes of sacked workers scuttling for the tube, cacti under their arms. And with the installation of Gerrard’s work – commissioned by Art on the Underground, Transport for London’s excellent series of installations in and around tube stations – the subterranean becomes both literal and metaphorical.

Gerrard’s piece, entitled Oil Stick Work, has been shown before, perhaps most notably on the island of Certosa during the 2009 Venice Biennale. In Venice, Gerrard’s piece – a real-time digital animation of a desolate Kansas landscape as setting for a Beckettian drama of fruitless labor – looked like a sober corrective to some of the splashier efforts of artists in the Giardini, like a guy tapping his watch at a party, encouraging everyone to get their coats and leave. In Canary Wharf, the virtual nature of his work takes on a poignancy provided in part by the site itself, the nexus of virtual transaction, of imaginary amounts of money swelling and falling every second of the day.

We see a large white barn with adjoining silos in an otherwise utterly deserted, dust bowl landscape; there are no other buildings, but telephone poles and a single empty road that swings out of the frame allude to a connectedness that’s important for the piece’s resonance. The realism of the image is initially startling, but the size of the projection – it takes up a huge temporary wall (12 by 8 meters) occupying one end of the vast station interior – crumbles parts of the image into pixels. Slowly, the “camera” pans around the building, roughly at eye-height: its languorousness engenders an adjustment into the world of the piece. Earlier versions didn’t include this element of panning, but there’s a gain too: as a work of public art, its stealthy cinematic qualities require a pause too infrequently granted to bronze blobs and scattergun murals. You watch because, as connoisseurs of the moving image, you know that film rewards patience. Something will appear. Notice how many visitors cluster around a video screen at any modern art museum, regardless of its content (and how few stop at the paintings, at least those without audioguide tie-ins, but that’s another story).

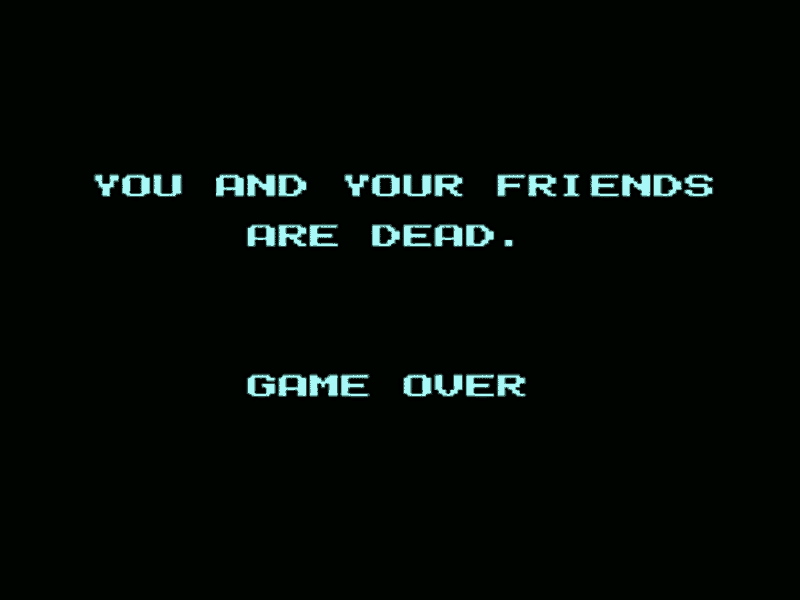

The reward is the appearance of a single character, standing on a retractable stairlift, engaged in an activity that’s initially hard to make out, but eventually reveals itself as intensive and very slow painting (or drawing, really; he’s using a black oil stick). Part of the barn is already painted the absolute pitch-black of a “game over” screen, and eventually (in 2038) it will be entirely black. Gerrard’s piece, which is more a sort of program, “started” in 2008 and is set to run (whether shown in a collector’s home or in a public space) for thirty years; every part of it is virtual except for time, which is entirely, painfully, real. The sun rises, the figure (based on and named after a real person, Angelo Martinez, whose movements were digitally transferred into the piece) arrives and works continuously until the sun sets, at which point he exits the screen. Set to Kansas local time, the piece’s only changing feature is the gradual blackening of the barn, which won’t be anywhere near completed by the time the piece is deinstalled in a year’s time.

Gerrard’s piece deals perhaps most evidently with the transience of commerce. Martinez’s action resonates with the expected phasing-out of western dependence upon petroleum during the piece’s lifetime; obsolescence is written into the script. Invariably, too, there’s a sense that the “real” work of Martinez — the subtext for the financial transactions taking place above ground — contrasts with the far more lucrative, though “virtual,” activities of international commerce. There are also parallels with the practice of art itself. Martinez’s perpetual activity – exhaustive, repetitive, solitary – is a performance of creativity of a particularly bleak nature. It’s a 30-year oil painting he’s making, ultimately — and isn’t there something Pollock-like about that barn, lodged in the American emptiness? Office workers ascending and descending the vertiginous escalators will see Martinez every day, his painting growing with infinitesimal slowness. Gradually it will weave into the narrative of thousands of people’s days. Gradually the barn will disappear, and its disappearance — its three-decade fade-out — is really what makes the work worthy of the “time-based” tag. A truly “time-based” art must articulate what time’s presence in art always has (from guttering candles to rotting fruit to quivering bubbles): its end.