I’m sure (as in: I’m not sure) that there is a film in which Laurel or Hardy or Buster or Harpo rides a horse backwards, isn’t there, maybe after being dropped onto the horse from a branch that suddenly snapped? And the horse bolts off? Or is that City Slickers 2: The Legend of Curly’s Gold? This sort of thing—a pleasurable and slightly frustrating rummaging through the old boxes of cultural memory, on hands and knees, pitching old photo albums and team building t-shirts back over your shoulders—happens to me pretty much every time I see something by Rodney Graham. As Shepherd Steiner put it, “it’s all so personable and relaxed it is easy to forget one is in the presence of art.” That being, I think, more or less irrefutably true, given the meticulous care (and what an underused idea in contemporary art that is) Graham lavishes on his art—both in terms of high production values and a kind of laconic, but earnest, philosophizing—Graham seems an obvious contender as a maker of public works of art. His 1986 Millenial Project for an Urban Plaza—a camera obscura set up to project an image of a sapling planted alongside it, designed to be returned to over time (so that the tree,projected upside-down, grows to eventually fill the frame)—was (as far as I know) never quite realized as planned. So it’s a heartening sight to see Graham’s copper Erasmus Weathervane atop the roof of the newly reopened Whitechapel Art Gallery, glittering and revolving and setting off all sorts of high and low cultural associations as it does, fireworks style.

In keeping with Graham’s M.O, Erasmus Weathervane is an adaptation—even an expansion—of several previous works by the artist. One is a 2002 black steel weathervane after a drawing by Derek Root, which depicts a silhouetted figure (the artist?) riding a bicycle backwards, which in turn derives from his Photokinetoscope film, which in turn probably comes from something else I/you can’t quite remember. The other is his 2005 Allegory of Folly: Study for an Equestrian Monument in the Form of a Wind Vane, one of his carefully staged self-portraits, here dressed as Renaissance theologian/humanist Erasmus, seated backwards on a training horse, brow-furrowedly reading the Vancouver phone book. So the London weathervane is a distillation of his earlier ideas, just as his ideas are distillations of somebody else’s earlier ideas. It’s easy to see this as part of a general ur-idea in Graham’s work, which is a kind of Beckettian tragicomedy of endless repetition. An uncharacteristically still day in Whitechapel had stabilized the thing when I first saw it. But imagine it wheeling around, Erasmus and his horse facing opposite ways, in a high wind, the speedy blur creating a visual illusion of coherent vantage between steed and rider, and the comic/philosophical meanings become both eloquent and effortless, which is Graham’s characteristic artistic sleight-of-hand. The mind and body are traveling literally at cross purposes. It’s a riff on the hoary old mind-body dichotomy still best summed up by Morrissey: “Does the body rule the mind or does the mind rule the body?/I dunno.”

All this is very nice and good and would be enough were it not for the additional associations that necessarily accrue to the figure of Erasmus in London. It might be coincidence, although I suspect not, that 2009 is the 500th anniversary of Erasmus’ most celebrated work, The Praise of Folly (written in London). In Rotterdam (Erasmus’ birthplace) at the beginning of this year, the Museum Boijmans-van Beuningen (note Graham-esque Christ on a donkey) staged a show of art associated with the writer, which inevitably brings to mind the painter Erasmus supported in his pretensions to work in England, Hans Holbein the Younger, whoillustrated The Praise of Folly. And it was Holbein who gave the English Tudor court its aesthetic identity via his portraits of Henry VIII and his court, and 2009 is also the 500th anniversary of Henry’s accession to the throne. The Tudor court placed special emphasis on heraldry, from which weathervanes also originate: the term derives from the pennants (“fanes”) attached to the tops of knights’ lances. So these things accumulate.

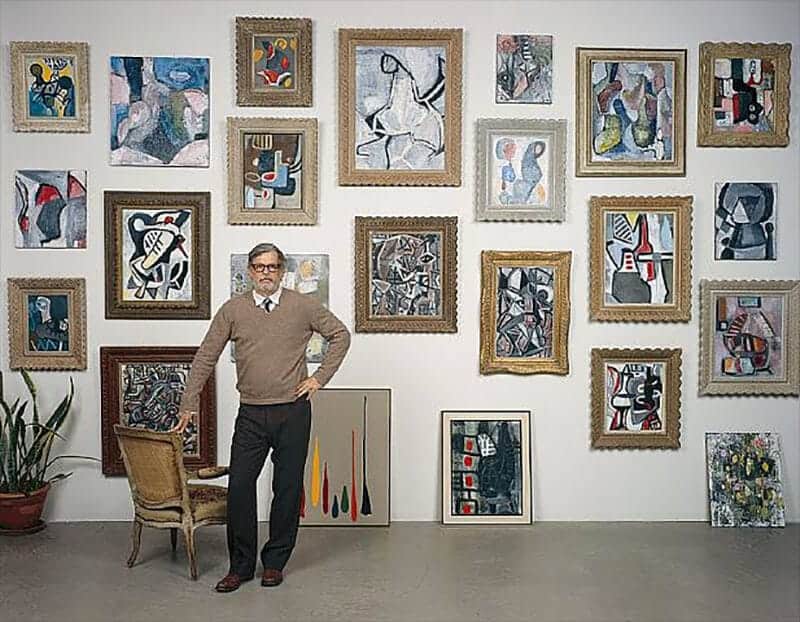

What I think is really interesting about this confluence of self-referential iconography and a historically loaded place and time is the light it sheds on Graham’s body of work as a whole. Erasmus, the perennial expat, roaming from Rotterdam to Paris to London to Basel, is a dead ringer for Graham’s flaneur/cowboy stand-in in his film How I Became a Ramblin’ Man. The Praise of Folly, with its sarcastic skewering of the conceit of the powerful, has strange resonance in Graham’s work too. As paraphrased by Bertrand Russell, in Erasmus’ terms, “it is easier to imagine oneself a king than to make oneself a king in reality”; this is reminiscent of the artist’s deadpan dressing-up throughout his career. Erasmus as troubled, ironic loner is a cousin of Graham’s lonesome Robinson Crusoe in Vexation Island, perennially concussed by a falling coconut. It’s hard to imagine that Graham isn’t aware that the European student exchange organization—sending troubled, ironic loners out into the world—is called the Erasmus programme (one of Graham’s great songs is entitled Never Trust Anyone Over Thirty). And, finally (but probably not finally, Graham being Graham), take a look at this image from Holbein’s illustrated Folly. In it, a merchant, distracted by a beautiful woman, walks headlong into a market trader’s basket of bread. It is, unwittingly, a neat distillation of Graham’s great theme: the cycles of idiocy brought out by the brain and body’s co-habitation.

These things accumulate, after all.