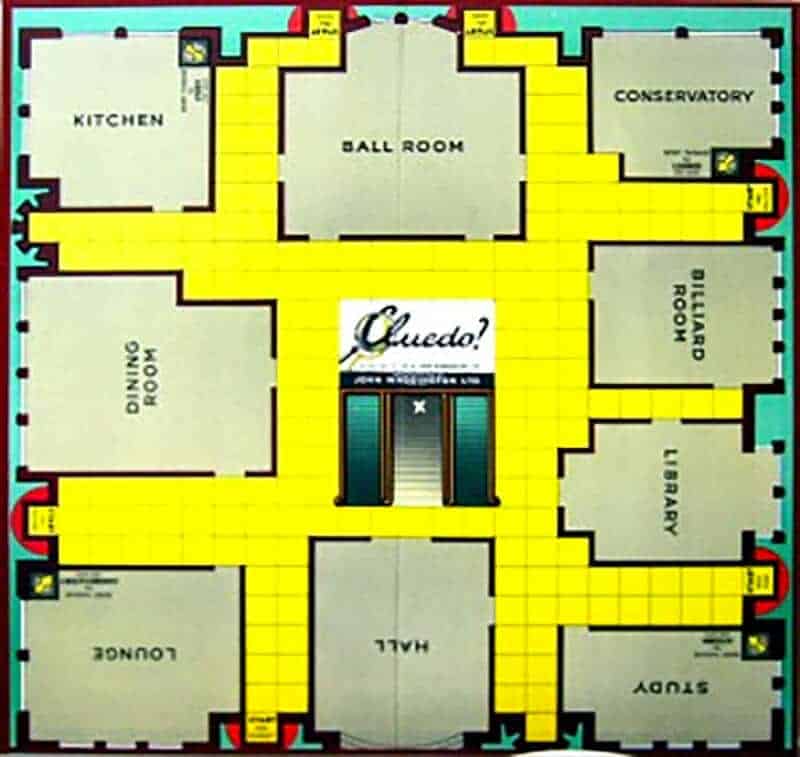

My favorite things in Pallant House, the excellent gallery of modern British art in Chichester on the south coast of England, are a couple of small models made before its reopening in 2006. Each model is a dramatically scaled-down version of one of the principal rooms of the gallery, about the scale of a train set or civil war diorama. Inevitably, one model is of the room you’re standing in as you stoop down to look, and hung on the mini-walls are mini-versions of the works of art around you (by artists like Peter Blake, Anthony Caro, and Patrick Caulfield). Sadly, there’s no succession of mini-yous and mini-models telescoping into infinity. But here’s the great thing: all of the works are mini-versions by the artists themselves! So, peering through the Plexiglass fourth wall, you get that God-looking-down-on-His-creation satisfaction that all curators must feel when they’ve finished shuffling the pieces around with long rods, Churchill-style, in low-lit backrooms thick with cigar smoke (note to self: may need to meet an actual curator one of these days). I’ve always loved the picture — Google Images doesn’t sympathize — of Bill Rubin in his curatorial wheelchair, jabbing at little images of Picassos as his minions scamper to rearrange their placement according to his magisterial will and booming baritone (see note to self, again). Curating as an idea is a kind of intellectual board game: metonymic tokens are pushed around an artificially sequential space. Think of the similarity between the Cluedo (Clue) board and the standard museum layout. See? Like a game (and like a mix-tape, now I think of it), curating imbues its players with an inflamed sense of personal agency usually denied in social settings (I should know).

The English art critic David Sylvester used to create fantasy cricket teams composed of famous artists – Vermeer in the slips, Michelangelo at the wicket – which draws a pretty convincing parallel between the world of curatorship and that of the fantasy sports leaguer. And although my dream museum pairing, Poussin’s The Seven Sacraments placed alongside a row of Judd’s aluminum boxes, won’t happen unless a serious clerical error occurs in the HR department of a major art museum, capricious artistic pairings occur naturally anyway, in the way that we experience and process works of art. Two recent shows in London are a case in point: the two artists have never (as far as I know) been shown alongside each other, but their conceptual and aesthetic similarities, compounded by a mulched and misfiring memory for what I saw where, have created for me a kind of ideal model of curatorial strategy. So let’s assume that the two shows, Mark Wallinger at Anthony Reynolds and Rodney Graham at Lisson Gallery, were in fact just one, as I shuffle the pieces around from the comfort of my wheelchair.

There are an unexpected number of resonances between Wallinger and Graham that might justify this mnemonic mix-up. There’s a shared interest in the symbolism of horses, for instance, as tropes of progress and archaism (Wallinger’s real horse, A Real Work of Art, his paintings of thoroughbreds, his giant fiberglass horse for Ebbsfleet; Graham’s backwards-facing Erasmus in its varied guises, his cowboys and cavalrymen). There’s a common probing of theatricality in relation to modernism (MW’s film of the artist in a bear suit, stumbling around Mies’ Neue National Galerie; RG’s modernist painter, listlessly making sub-Nolands in a sub-Neutra living room). There are projects that reconstruct historical events through their relics (MW: State Britain; RG: Lobbing Potatoes at a Gong (1969)) and are filtered through assumed identities (MW’s “Blind Faith,” the artist as blind man; RG’s Country Self/City Self), and so on. Both artists address the way we understand and process the past through experience-filtration devices (rock music, travel, cinema, photography, art, sport).

These recent works bear comparison too. In Wallinger’s I Am Innocent, a double-sided reproduction of Velazquez’s Innocent X portrait rotates thrummingly, like a pinwheel in an encroaching storm. Thus zoetroped, the spinning image doubles itself, becoming a looped dialogue between selves, a kind of double portrait. Graham’s Good Hand Bad Hand, two adjacent lightbox photographs, shows the artist doubled in two self-portraits as poker playerwith cap, sunglasses, and inscrutable frown. The gag of the title – it’s a pair, so it’s a “bad hand” in itself – isn’t its only common ground with the Wallinger piece: both works probe the notion of the “tell” prized in 17th-century portrait painting and deplored in 21st-century poker playing.

That papal portrait, so inextricably linked to conventional ideas of absolute authority that it obsessed the atheist Francis Bacon in the mid-20th century, has its modern equivalent in authoritarian propaganda. Bertelli’s Continuous Profile of Mussolini (which featured in Wallinger’s curatorial debut, The Russian Linesman, at the Hayward Gallery) – a portrait bust in apparently frozen rotation – resonates too with the other work in Wallinger’s show, Self (Times New Roman). A tall black cylindrical column, which on inspection is an uppercase letter ‘I,’ appears to spin before your eyes. It’s a self locked in a loop, like Graham’s lighthouse keeper, toasting his feet at an open stove, a scale model of his lighthouse on the table behind him.

There’s even a similar model to the Pallant ones in Graham’s show. In it, a lone figure – an action figure of the latest incarnation of Dr Who, Matt Smith, for no reason I can confidently fathom – stands in heroic puzzlement in the very space you stand in as you see it, looking up at a jigsaw of modernist shapes whose larger versions fill the room around you. Like the Pallant models, Graham’s work engenders a kind of perceptual flickering between actual and imagined scale, between curator’s and visitor’s eye view. That idea – the relative scale of real and imaginative space – is a well-established tragicomic trope in Graham’s work as a whole. But it’s also a way of thinking about art: that the real space of the gallery is the pristine little model your mind stoops to see, and what lives in the mind is a cathedral by comparison.