The apparent serenity of Rachel Kneebone’s white porcelain sculptures is belied by the physicality of their making. “It’s war”, said the artist, when asked to describe her process. The manipulation of the messy slab of clay – gouged and kneaded into shape in no fewer than two days, “or the material starts going crumbly, like Wensleydale cheese” – is nowhere evident in her delicate, poised, intimate works. At least, that’s how it initially appears. On closer inspection, and you really do have to get close, her sculptures rapidly shed their prettiness. The heads of recumbent figures erupt in bouquets of labial folds. Elegantly repoussoir bodies taper into veiny penises. The Dionysiac abandon of her works’ content is always held in tension with the Apollonian clarity of its form, just as the glossy patina of the porcelain’s surface hides, like a repressed memory, the messy business of its creation.

Kneebone’s commitment not only to a kind of figuration but also to a labour-intensive process makes her seem anachronistic within the typically outsourced practice of many contemporary artists. Her usual approach places in tension two modes of creation: the carved and the cast. On a press-cast clay plinth, a figure or series of figures is hand-moulded, their forms (which always, to some extent, derive from the image or experience of the human body) partly pre-determined, partly improvised from the given form of the material. There’s something of that formal looseness in the finished works, too: an atmosphere of delicately finessed playing-off of form and content. The forms that appear seem just-made, early stages of a kind of physical creation, still slick from the primordial soup, stilled in their metamorphosis by their own quick-drying matter. And despite the hardening of the material in the kiln, there’s nothing final about the appearance of Kneebone’s works. In a sense, they’re sketches that can never quite be brought to fruition, or ideas that never quite find the right words to be articulated, either through their horrifying truths or impossible suggestions.

Porcelain has such a low profile within the history of art as to be virtually invisible. Traditionally associated with decorative and playful subjects, it came closest to artistic credibility in the heady pre-Revolutionary days of rococo France, before being shattered (along with other practices too willing to sacrifice seriousness for frippery) by modernism. It would be easy, though misguided, to see a political stance in Kneebone’s assertion of an historically neglected material. The tradition of women artists’ co-option of overlooked, implicitly feminised practices – from Rosemarie Trockel’s embroidery to Judy Chicago’s porcelain platters – made way, in the British art scene of the 1990s, to a determinedly tough-minded and punkish approach to materiality, as seen in the work of Sarah Lucas and Tracey Emin. Unlike artists of that particular generation, whose work owes a singular debt to the aggressive aesthetic collisions of Dada collage and the altered readymades of Duchamp, Kneebone’s work takes a more poised and contemplative approach that gains sustenance from much earlier periods of art history. Nor does her work comply with the orthodox kitsch of Jeff Koons’ outsourced porcelain sculptures. Rather, Kneebone’s work returns to the unresolved questions of the past, employing perhaps the most ancient of motifs – the human body – as a means to explore and address questions of fundamental and transhistorical import. This description might seem to tie Kneebone into a wilfully regressive practice, but it’s a mark of her unique qualities as an artist that both her formal and philosophical concerns, though ancient, seem renewed and revitalised in the strangeness of her work.

The delicacy of her given material is intrinsic to the meanings of Kneebone’s works. The possibility of self-destruction lurks, perpetually. Her figures, unsupported by an armature, drape their long limbs outwards, as though tempting their own demise. As moisture is drawn out of the material in the kiln, its dehydrated mass can shrink by up to 20 per cent, causing easy snaps and splits. To some extent, Kneebone exploits this threat, encouraging her press-cast plinths to develop spidery cracks by piercing their sides before the firing process. This danger becomes meaningful, too. Works like Et in arcadia ego, with its curl of slim porcelain drawing the composition to a fevered crescendo, perform their own titles: death and destruction are here, even in this cradle of intricate beauty. Perhaps even especially here.

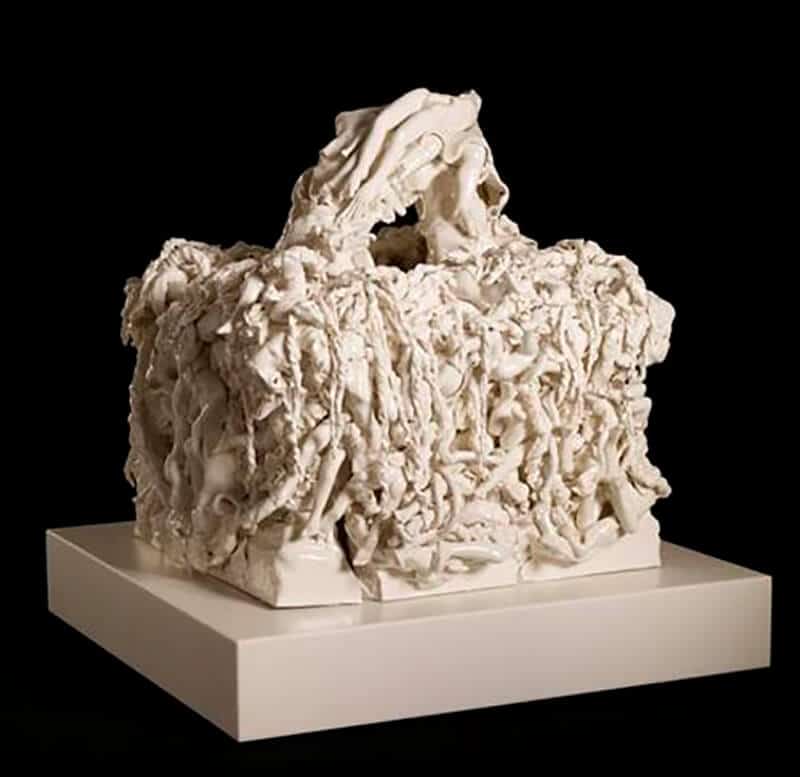

The sepulchral plinths, whose crumbled forms provide a textural contrast to the serpentine bodies that writhe above them, suggest the melancholy presence of mortality amid the fiesta of flesh, the thanatos to the figures’ eros. Classically robust, with a simple dado and cornice, they act both as stage and narrative context, suggesting resurrection as well as pictorial archetypes of melancholy. That parallel is made most apparent in her cover version of Michelangelo’s presentation drawing The Dream of Human Life, in which the reclining ignudo of the drawing has transformed into a legged cock. Kneebone’s figure, like Michelangelo’s, is propped by a plinth, touchstone of classical melancholy, and leans against a large ball (which, in Kneebone’s treatment, seems decidedly testicular). As in Poussin’s painting of the same name, the plinth in Kneebone’s Et in arcadia ego is the materialisation of heavy thought, a dead weight like an anchor. It’s this suggestion of the weight of melancholy – a notion suggested by the plinths’ blocky forms, in ironic contrast to their physical lightness – that animates Kneebone’s The Descent, in which the plinth seems to have sunken into the earth, creating a vast, Sarlacc-like pit into which her doomed characters tumble and fall.

Given her works’ refusal to resolve itself into a single, determinable meaning, drawing has an unusual role within Kneebone’s approach to art making. Unlike its conventional usage within the history of art, and with the exception of very large works such as The Descent, Kneebone does not use drawing as a rehearsal for sculpture. This is a function of her commitment to the possibilities provided by the material itself, and her avoidance of the pre-emptively ‘finished’. Rather, her drawing can be seen as a parallel practice, something not inferior to but in concert with her better-known porcelain work. In other words, it’s all drawing – specifically, drawing’s associations with the exploratory, the private, and the experimental. In a drawing like En pointe, a scenario impossible to imagine taking material form – namely, a star of stretched legs enacting the ballet position of the title, which bursts out of a series of orifices; a fat penis slumps out too, a pearl of liquid emerging from its slit – is enacted. Partially resolved lines half-describe a form redolent of Hans Bellmer’s drawings after de Sade, but where Bellmer used the specificity of the drawn line to limn a pedantically detailed vision of sexual depravity, Kneebone never quite allows her image to complete itself. She stops short just before language makes her imagery possible.

Kneebone has said that her work treats a figurative subject as though it were still life, which points to the manner in which contemporary artists address the themes of the past. Rather than employing the generic conditions under which still life came to be regarded as a separate category in the seventeenth century, Kneebone treats the genre as a physical experience. The traditional scale of still life painting is as small as its subject was humble, obliging an intimate relationship between viewer and viewed: unlike larger-scale paintings, still lifes are usually viewed by one person at a time. Similarly, Kneebone’s work – much of which, forced by the delicacy and low tensile strength of her chosen material, is no bigger than a basket of fruit – has all the held-breath intimacy of a Chardin still life. That physical relationship between object and viewer is energised all the more by the tactile quality of the material itself. The porcelain’s all-white tone (underscoring her works’ sense of perpetual becoming: it hasn’t worked out what colour to be yet) and glossy glaze encourage a particularly intimate kind of touching: you want to stroke, not grab; caress, not grip. It’s the kind of touch that knows it’s a step away from damage, and is tantalised by that knowledge. Furthermore, porcelain’s association with everyday objects – plates, cups, bowls – is a reminder not only of the artist’s engagement with the history of still life but of her profound interest in the relationship between the body and the world. Porcelain tends to be used for objects that have a close physical connection to their users, and often one associated with intimate or private functions, from false teeth to toilet bowls. Kneebone’s work, then, deals with bodily experience, in both form and content. It feels close.

To claim that figuration died out in the wake of abstraction is to misunderstand the role of the human figure in art’s philosophical maturation. Kneebone’s use of the human figure as a starting point in her work is a reminder that the best way we have of understanding ourselves is through ourselves. Her work’s principal philosophical motor is the same as that of all art of the past: as the artist herself puts it, “How do you make an idea?” It is apparent that, whatever ideas Kneebone purports to be exploring in her work, their crystalline articulation is by no means a priority – or, better, they’re ideas that can’t be conventionally articulated. In In the midst of quietness branched thoughts murmur (2007), a sort of grotto of intestinal tendrils sits atop a cracked circular plinth. Grotesque, part-figurative forms – they start as splayed legs and end as peaked labia – sprawl listlessly around, or stomp blindly across the tiny landscape. Their appearance, as though having recently emerged from the mass of slimy caves in the grotto’s centre, seems to have been suggested during the work’s own creation: the construction and the apparent subject seem bound together. In this way, Kneebone’s work recalls Max Ernst’s Surrealist decalcomania from the early 1940s, in which intricate, mazy grottoes emerged via an automatic process (in his case, the squidging of wet paint on a surface by means of a sheet of glass). Kneebone’s work has a significant kinship with Surrealism: its employment of aesthetic surprise – the sudden appearance of disturbing or sexually troubling imagery within an apparently innocent milieu – has visual parallels with her interest in Andre Breton’s ‘convulsive beauty’. And yet Kneebone’s work eschews the rebus-like Freudianism of Surrealism at its most literal. Rather, her sculptures employ a form of automatism and grotesquerie familiar from early twentieth-century art in order to probe a very contemporary array of anxieties.

Kneebone’s work should be approached in the spirit of its titles, many of which – with their odd capitalisation and absence of grammar – recall their origins as found lines from existing texts. This literariness is carried through across the artist’s practice. An intricate spider-chart of written references, allusions and ideas pinned above the artist’s desk was described as a “drawing”; starting-points for sculptures range from Blanchot, Bataille and Peignot to Dante and the Old Testament. Kneebone claims never to consider her contemporaries’ works, and is baffled by allusions that seek to place her in line with other “young British artists”. Instead, her inspiration comes largely, though never entirely (the material and its curious demands have a dominant role within the development of any given piece) from an experience of reading, a practice whose privacy and imaginative fecundity seems mirrored in the forms of the works themselves. There’s nothing illustrative, however, about Kneebone’s work. Instead, her sculptures can be said to explore timeless narratives that address the experience of death and the life beyond, whether that’s Dante’s Divine Comedy (explored in The Descent) or the theme of the death and resurrection of Christ (implied by her sprawled forms on tomb-like plinths). Her works turn on ideas that are both essential and irresolvable: how does death feel? What does it look like?

Christological themes are an undercurrent in Kneebone’s work, partly for the same reasons that Francis Bacon employed them: as he put it in one of his famous interviews with David Sylvester, the crucifixion was “an armature on which to hang certain emotions”. Like Bacon, Kneebone often employs the triptych format familiar from medieval altarpieces, and makes reference to the transfigured body of Christ as a kind of metaphor for the human soul labouring under modern conditions. For Bacon, the contorted human form, painfully isolated in space, was a symbol of western barbarism in the wake of World War Two; for Kneebone (whose name has Bacon’s own apposite corporeality, and whose works you suspect Bacon would have loved), the bodily distortions are a trace of a kind of mortal anxiety felt through and inextricable from the body. Kneebone’s works enact, on sepulchral stages redolent of death, in poses redolent of life felt at maximum physical intensity (the legs strain and buck, en pointe), the body locked in – bound by – thought. Tensed, sweat-sheened, they lunge at the inexpressible, the impossible, seeming to perform Andrew Marvell’s lines in ‘The Definition of Love’:

My Love is of a birth as rare

As ’tis, for object, strange and high ;

It was begotten by Despair,

Upon Impossibility.

- Originally published in ARS Magazine, Issue 10, 2011